Play-based mathematics and safety

- Dr Helen J Williams

- May 5, 2020

- 8 min read

Several things have come together this morning for me to be able to write this blog.

· Firstly, a request that has been sitting in my in-box for a few days for something on why play-based tasks might be important for the older learner (and by default, for any learner),

· Secondly, a series of tweets from parents about how their children were finding learning at home, and;

· Thirdly, learning in places of safety. Pondering how I continue to influence the talk around mathematics so that every interaction, with every child, results in them thinking positively as themselves as mathematics learners.

I will keep this as short as I can (!), with the objective it helps us all to think about and discuss these, what I believe are important, issues. Finally, there are some tasks I think illustrate the spirit of what I am arguing.

These ponderings stem from some conversations – mainly typed to be fair – that have taken place with people, educationalists, teachers, parents, whilst we have been in lockdown for these past weeks. These have revolved around discussions of what maths might look like currently in a small ‘class’ consisting of all ages of child 4-11 and what constitutes effective and purposeful home-learning tasks. These issues are related and linked to why I believe so strongly, that play-based mathematics is essential for children outside the EYFS and well into KS1 – and in fact, into KS2 and beyond.

I’ll start by attempting a definition of ‘play based learning’. For me, this is teaching that allows some space for sense-making. Teaching that deliberately seeks out tasks that allow every child to make a start, to make a continued contribution. Teaching that does not rise too steeply, too quickly. Teaching where my - often many - prepared questions do not come too fast, one upon another. Teaching with gaps for playing with ideas, on paper, by thinking alone, by talking, and mainly, by manipulating – playing with - materials. Teaching that allows space for me to observe and thus, assess, next steps. Mathematics that contains an essential ingredient of ‘healthy work’:

“Healthy work – that is, work which is seen by the participant as enjoyable, purposeful, creative and rewarding, – the essential ingredient of play: the facility for becoming absorbed, for loosing oneself in the activity.”

(Brown, 1996)

Why playful mathematics outside early years and the EYFS?

My position is clear. Being playful in mathematics is critical for creating a safe, risk-free environment for children to operate mathematically. If something is approached as a game, as an exploration, through pretence or via a story, children can try out ideas and make suggestions without fear of failing. They learn they are as important as the mathematics. I have observed this happen on numerous occasions and in many varied contexts, with every age of learner from 3 – 11+, with children who favour pages of calculations, with children who have been ‘turned off’ mathematics for years, as well as with very young children; and through the use of dice and games, role play and allowing time for (playing with) manipulatives.

I have also observed the following. Between the ages of 5 and 7 years, over-emphasising the answer or the ‘correct’ procedure can cause children to become obsessed with not making a mistake or ‘doing something the right way’ and ultimately fearful of maths. Here: https://info125328.wixsite.com/website/post/roller-skating-or-tidying-which-is-mathematics-to-be I discuss the problems of an approach to mathematics that overcorrects, that steers children closely through a series of small, pre-determined steps, that carefully avoids the making of mistakes. Sue Gifford similarly describes well here how to create a generation of mathematics lovers: https://nrich.maths.org/11441

Research (Askew 2010) points to learners of all ages, and of all attainment levels, in all jurisdictions, having negative attitudes to mathematics. This, rather than being counter-intuitive, is understandable. When higher attainers or those viewed as ‘successful’ mathematically are seen as always correct, they have a lot of face to lose by risking making a mistake. Their option might be to stop taking a risk, to stop engaging in harder challenges; to stop playing mathematically.

Home learning.

Here is @sue_cowley ‘s original Twitter question:

"Question for #parents - is anyone else finding that their kids are enjoying approaching the different subjects at their own time/pace?"

Reading the thread there are several replies that would be worth considering at a staff meeting. Parents reporting tantrums from children who can’t solve a puzzle immediately, whose children resent any time at all spent on schoolwork, 5 year-olds hating the maths inputs, and this from Rosanna (@RRaimato) whose reply struck me as particularly pertinent to mathematics:

“Things my son kept telling me he was ‘rubbish’ at, he is actually fine with. Discovered it is more about anxiety from his perception of pressure of questioning and not wanting to make mistakes in front of classmates. He says he feels safer and more relaxed.”

I realise that none of this is easy and that for every example of a child who is benefitting from one circumstance, there will be another example of a child who is not. However, this is our opportunity to really examine what we want from our schools and education. Rosanna goes on to say that the whole experience: “...has really made me think about concepts of ‘safe’ for learners.”

Safety

This is something I have worked on for the 30+ years I have been involved in mathematics education. Having not had a very positive secondary school maths experience myself and coming late to enjoying maths has probably made me super-sensitive to the atmosphere that surrounds mathematics teaching. I talk about it here: http://www.mrbartonmaths.com/blog/helen-williams-early-years-teaching-and-manipulatives/

How I influence the language and talk around mathematics, sits at the centre of my planning. Mathematics has more negative narrative than any other subject. How am I helping to alter that? Every day, with every single interaction?

This is where playful mathematics sits. It allows the learner in, and I agree with Simon Gregg (@Simon_Gregg) when he says: “I think it also helps those students who like the routine, one answer stuff.” It’s not helpful for learners to think of mathematics as simply a one correct answer fast, subject.

To change that narrative I need to make sure the mathematical diet I provide my children – at home or at school – is varied and is woven through with a strong thread of exploration and play. So much of what I am seeing in online lessons does not do that. What are we teaching our children about our subject by only providing a diet of ‘do this, practice this, now a ‘quiz’ to see if you remember it’?

We do want them to want to come back to school, don’t we? We do want them to want to do maths?

If we want to raise a generation of confident mathematical thinkers we need to embrace mathematical playfulness. Being playful in mathematics is about opening up what we offer to children to work on so that more than one solution is possible, where there is some space for them to tackle the task in different ways. I must make sure I don’t simply jump on and reward correct answers. Make sure that my mathematics classroom and my teaching moments are always safe enough for every single child to make a contribution.

Children need the time and space to play with concepts, and playful tasks are perfect for doing this. What follows are some ideas for playful mathematics for slightly older children that can take place at home, or indeed, at school.

- All the @NrichMaths tasks have a playful element and run from 3-16+

They are written and trialled by teachers and there is a parents and children’s sections to browse.

- Take this video task posted from @surfmaths https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=8&v=BvDXxdJ7ZfY&feature=emb_logo

‘Write your name using 50 matchsticks’ (we could use cocktail sticks or Lego bricks.)

This is a fine example of playful maths that can be tackled at many levels. Up my sleeve I might have follow-up questions such as: ‘Is there a different way of doing that?’ “What about your whole name /just your first name?’ ‘What could you try now?’

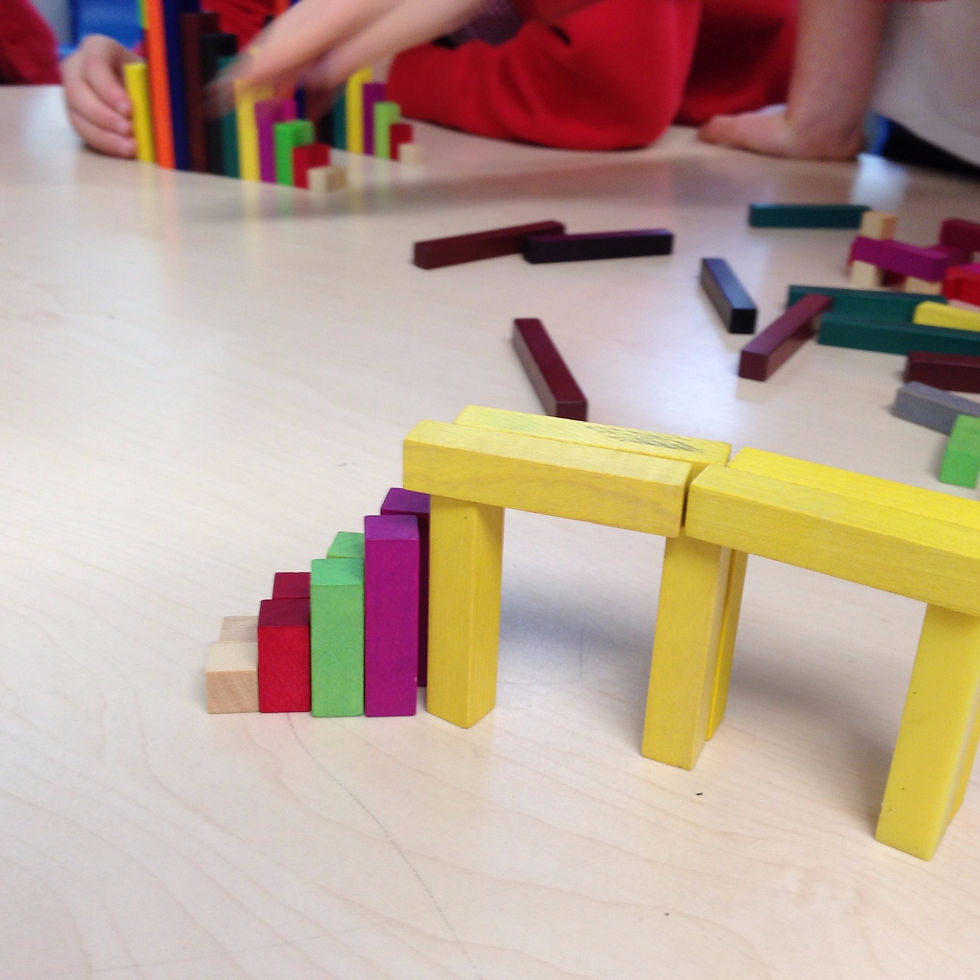

- ‘Make the same’ is one of my favourite tasks, for all ages.

To begin we only need to share a variety of bricks and play-people between the two players, so that we each have exactly the same collection. Add a large book to act as a screen between the two of us and we’re away. Player 1 uses all the bricks to build a scene and gives instructions to player 2 so that they ‘make the same’. Only player 1 is allowed to peep over the screen until they are satisfied both models are indeed the same.

This is much harder sitting back-to-back with identical interlocking bricks of the same colour, or tangram pieces!

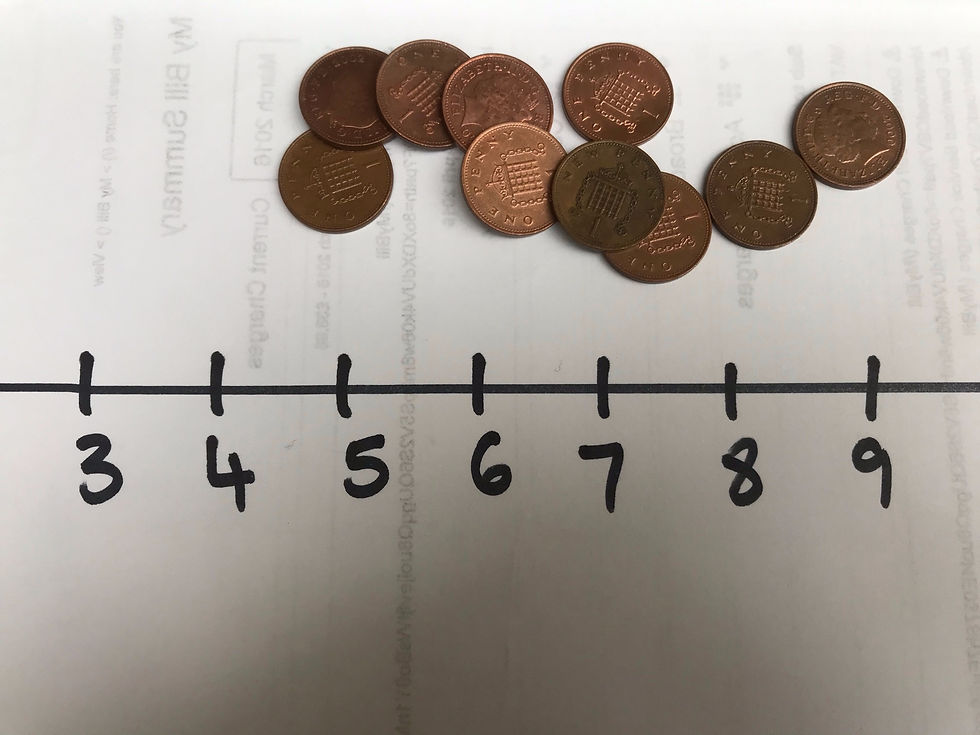

- Two Dice Game. You need paper and pen, 2 dice, and 10 counters each.

Draw a line and write the numbers along it from 2 through to 12. Each player takes 10 counters and places them on their line so that …. When we roll both dice and call out the total, I can remove one counter from my line. If I roll a 3 and a 2 I call out “5” and remove one counter from the 5 on my line. The object is to remove all the counters from my line before you do. Where do I place my counters so I win? Spread them out? Bunch them up on certain numbers? It is important that this plays out without someone telling someone else the ‘answer’!

What do you notice? What will happen if… we play again? What about if… we subtract the two dice numbers, where to place the counters then?

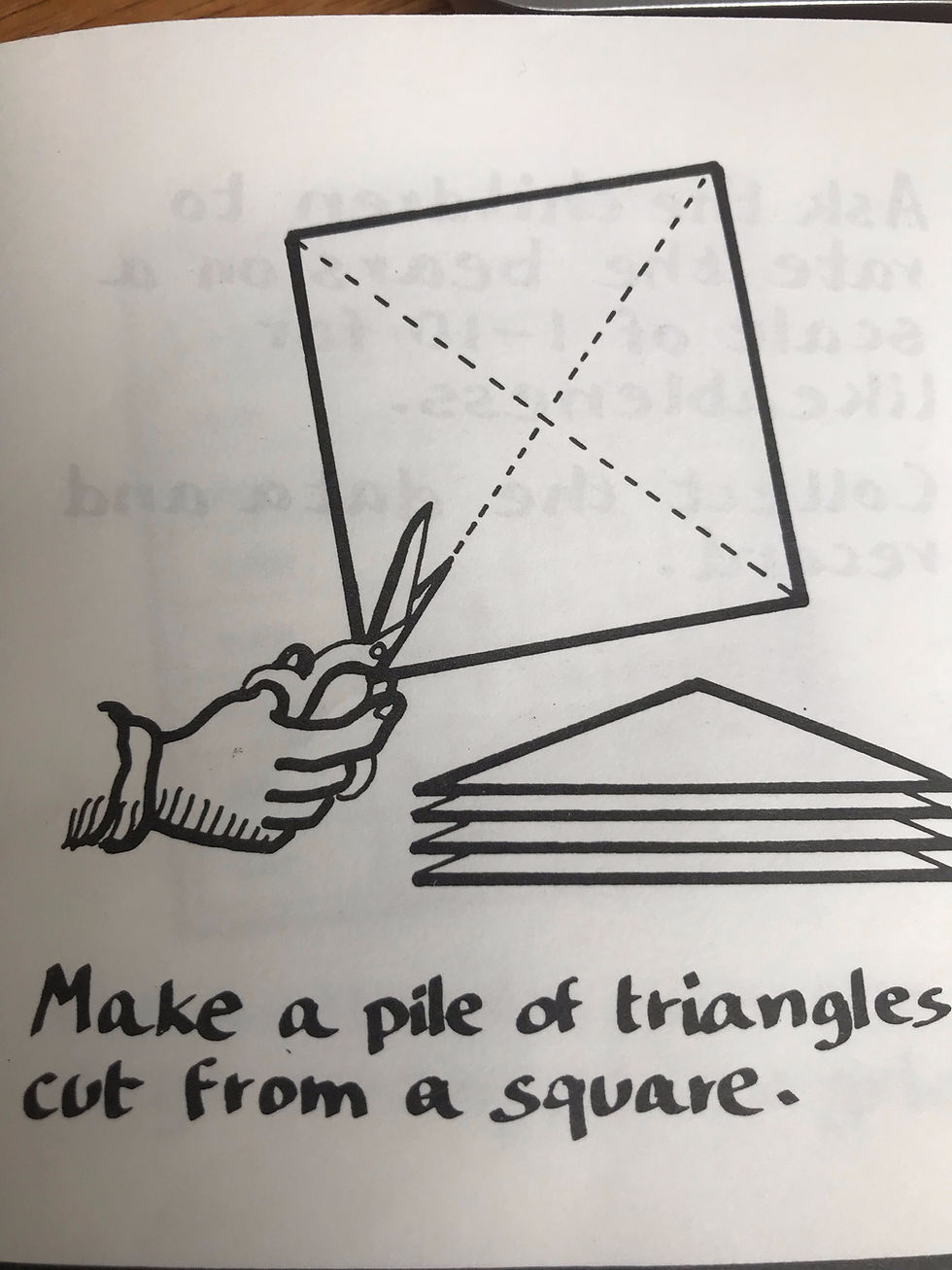

- Squares. Cut a square into 4 pieces by folding into ‘sandwiches’, corner to corner.

(ref: ATM, 2017)

What different shapes can you make by fitting the 4 triangles together? What are your rules for joining the triangles? What about making ‘holes’? What if… you use only 3 triangles? How can we keep track of the shapes we are making? What is the same / different about this shape and this shape?

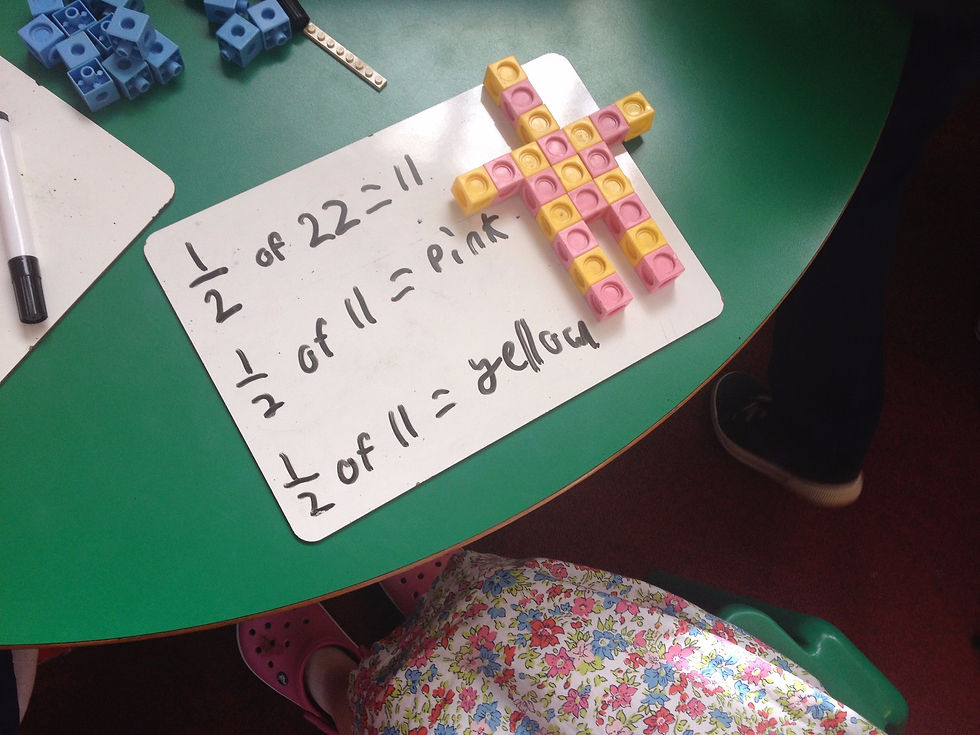

- Fractions. You need quite a lot of interlocking bricks all the same shape and size, in 2 colours.

Make a shape that is half one colour and half another. How about 1/4 ? How do we know for sure that this model is half blue? Take 12 bricks only. What other shape-fraction models can you make?

Noddings (1984) argues that the teacher’s task, whilst operating under an ethic of caring, is to receive and accept students’ feelings towards a subject as part of their response to what is taught. Her argument is that if we achieve our ends instructionally, but the student hates the subject, then we have failed educationally. Being and staying safe needs to be a mantra we take from this truly awful situation we are all in at the moment and into out mathematics classrooms.

I welcome responses to this. Here or on Twitter.

References:

Askew, M., (2010) ‘It ain’t (just) what you do: Effective teachers of numeracy’ in I. Thompson (ed.) Issues in teaching Numeracy in Primary Schools. Maidenhead: Open University Press

ATM (2017) 'Exploring Mathematics with Younger Children'. 2nd Edition. Derby: ATM

Brown, T. (1996) ‘Play and Number.’ In: ‘Teaching Numeracy: maths in the primary classroom’ (Ed Ruth Merttens). Leamington Spa: Scholastic

Gifford, S. (2015) 'Early Years Mathematics: How to Create a Nation of Mathematics Lovers?

Age 3 to 5.' NRich https://nrich.maths.org/11441

Noddings, N., (1984) Caring: A feminine approach to ethics and moral education. London: University of California Press

Footnote:

Here https://info125328.wixsite.com/website/post/a-mathematical-bucket-list-for-under-fives-and-beyond I describe some tasks – a mathematical bucket list – for under five year olds.

Here http://www.mrbartonmaths.com/blog/teaching-from-home-helen-williams-supporting-early-years-students/ I talk to @mrbartonmaths about home learning and younger children and explain why I am unhappy with the term ‘home schooling’, preferring the term ‘home learning’. It is important that right now families don’t feel under pressure to recreate school at home, for families to not feel they have to fit into a school timetable. And for parents and carers not to pass what maybe their fear of mathematics on to their children.

Comments